by Robert Mazzucchelli | Mar 1, 2019 | Forever Learning

Two years ago, I co-founded SportsEdTV with a bunch of really committed and smart people. I am learning so much every day from this experience about building a brand in the cyber world, and wanted to share some of my revelations.

After decades of marketing hundreds of brands in as many categories, SportsEdTV represents the first purely digital product I have promoted, meaning the entire experience – from marketing to product engagement – happens online. Users discover the brand online, engage with the brand online, and share the brand online. Only occasionally, do they encounter the brand offline, when they meet one of our coaches on the court or field, or in the gym.

SportsEdTV is aggregating a global community of athletes, coaches and parents across the world, and providing them with free world-class video instruction in over forty sports, as well as a forum for learning and meeting other like-minded people. If you play a sports at any level and want to improve or interact with other athletes, this online destination is for you. Or, as our tagline says: SportsEdTV. Making You Better. Anytime. Anywhere.

So, what have I discovered while launching this brand?

1) When launching a digital-only brand, you are a global brand from day ONE. Be prepared for a world-wide audience.

I am astounded that since we went live with our website six months ago, people from 130 countries have watched our instruction videos (and they are currently only in the English language!). There is no such thing as a gradual roll-out online. The roll out happens when you push the go-live button. When we launched, I assumed that mostly people from English speaking countries would be watching our videos initially, but about 60% of our viewers are from non-English speaking countries. This has forced our team to review all of our videos to make sure the lessons are easy to learn, even when the viewer only has some rudimentary understanding of English. We have used more graphics as a result, and more slow-motion repetition of key movements taught by our coaches. We have had to make sure to be culturally sensitive wit’s every word and action in our videos. No jokes that might offend someone because of the cultural or language barrier. For non-digital brands, a global roll-out can be planned in stages, with learning happening in each stage and applied to the next. Online, the timeline is collapsed and the world is your stage overnight. Literally. Be prepared.

2) Fluctuations in business volume can happen instantaneously. You need to be agile and move fast.

One social post or digital ad or blog post can have an immediate impact on user volume. This is good and bad, but it is a reality you need to assess constantly. In businesses where products are on a shelf, or are shipped to users, this process happens slower, and brands have more time to react and choreograph responses to events. But because our user experience happens entirely online and often in an instant from discovering the brand, I have seen small actions, like a share of a social post, spike views of a particular video wildly and almost instantaneously. Fortunately, I have not seen the opposite possibility, where a negative review or comment could tank the viewing of a video, but we are always prepared for either case. We can also cause a spike in viewing within hours when need be, so we are monitoring all viewing activity 24/7. Having a slow viewing day? Nothing a little boost in spending on Facebook can’t fix within a few hours. This type on instantaneous driving of a result, where you can find a potential user somewhere in the world, promote the discovery of your product within minutes and have them engaging with it immediately is a digital-only phenomenon. The good news of this digital-only reality is that you can manage business fluctuations easily and quickly. Agility matters. The bad news is that you, or your team, need to be watching ALL the time. Make sure you hire early birds and night owls.

3) Don’t overreact to individual data points, look for trends. Make data your friend.

Data is the blessing and curse of marketing today. We have more of it than ever before, yet much of it is useless in isolation and time consuming to wade through. In a digital-only business, data drives almost every decision and action taken. When we launched SportsEdTV, and I was presented with data from multiple dashboards on all sorts of viewer statistics and behavior, I was delighted and overwhelmed at the same time. Which data points mattered? Which data was more predictive? Which data could help drive product development? Which data could inform our ad spend? Which data could improve our website design? The questions are endless and created more than a few sleepless nights. Eventually, however, you find a rhythm to using data. You develop a sixth sense that helps you tune in to the data trends that really matter, based on the stage of development of your business. You develop ratios that represent the health of your business, and you start to figure out how the data can become a strategic and tactical friend, rather than an all-knowing, smothering adversary. If you are a digital-only business, find a way to make data your friend or you will not succeed.

It’s been only six months since our launch, and already I have learned so much. In fact, the team is in perpetual learning mode and that makes it fun to go to work every day. If you are in a digital-only, or even digital-first business, get tuned in to learning something new every day and applying it to your decision making. The internet is a fast-moving space in which to play, but it’s a great place to grow a big brand in a relatively short amount of time. More learning to share in my next post…stay tuned.

by Robert Mazzucchelli | May 25, 2017 | Lessons From The Passionist

(This is installment #9 of Lessons From the Passionist: How To Turn Passion Into Purpose To Create Greater Meaning and Joy in Your Life. Today we talk about the influence coaches can have on our passion, whether helping us find it or bring it back when it seems to be waning. Enjoy!)

(This is installment #9 of Lessons From the Passionist: How To Turn Passion Into Purpose To Create Greater Meaning and Joy in Your Life. Today we talk about the influence coaches can have on our passion, whether helping us find it or bring it back when it seems to be waning. Enjoy!)

For many people, coaches are a big influence in how they view and shape their lives. I’ve seen the impact in my own life and have heard countless stories about amazingly influential coaching relationships that have inspired lifelong passion in people. While the examples I highlight below are sports related, there are many other types of coaches who ignite people’s passion every day in business, relationships coaches, creative arts and many other areas of life. Coaches can be an important ingredient for living a passion-driven life.

The passion-stirring skill of many great coaches is well documented. Books have been written about them and movies made as well. Vince Lombardi willed the Green Bay Packers to greatness. Pat Riley created an NBA dynasty with the Los Angeles Lakers. Herb Brooks inspired a bunch of college kids on his 1980 U.S. Olympic hockey squad to find enough passion to beat a superior team of professional Russian hockey players in one of the biggest upsets in sports history, the “Miracle on Ice.” And Richard Williams could be considered one of the best tennis coaches in the world, having shaped TWO of his daughters, Venus and Serena, to be grand slam champions who are still at the top of the women’s game well into their thirties.

Coaches can help athletes, executives and other professionals see what they might be missing by being too close to the action every day, or they can help offer an alternative perspective of the things they are both seeing. High level performer always want that second opinion. Coaches can certainly help with technique, preparation, strategy and tactics. But they can also help inspire, instill and reinvigorate passion. Even the most passionate people cannot sustain their optimum level of passion all the time. Coaches can help identify when rest is needed or when a kick in the ass is needed. Great coaching is a vital source we can tap into to find and sustain passion throughout our lives. I would bet all of us has had a coach or two who helped us find a little more passion when we needed it most.

A few years ago, I was working on a project with a well know tennis coach and friend, John Eagleton. He had hired me to help write a book and direct a video series about Techne Tennis, a teaching method he had developed over his thirty years of working with players of all levels. Since I had experience as both a tennis player and a communication professional, I was able to translate his teaching into consumer/student friendly language, images and video footage. It was a fun collaboration that continues to this day.

John and I spent countless hours studying the movements of top tennis players and the movements of top athletes in other sports. We wanted to find a connection between the core athletic movements in tennis and those in other sports like baseball, football, volleyball, soccer, and boxing. That way, people who had played other sports could relate to and use these connections to learn tennis faster. Drawing these parallels proved to be a very effective teaching technique, and we’ve found that people learn very quickly this way.

One of the sports we had a particular interest in studying was boxing. Boxing has often been compared to tennis for its “mano-a- mano” nature, and the individual effort – not team effort – that dictates success or failure. They are both exhilarating games when you are winning, and extremely lonely games when you are not. But, while John and I were interested in the comparative mental aspects of the two sports, we were also keenly interested in comparing the rotational movements boxers make when they throw punches to the rotational movements tennis players make when they hit tennis balls (as it turns out, they are very similar).

One morning, John and I were having breakfast before heading to the tennis courts in Miami. Sitting next to us were two young athletic looking men in their mid-twenty’s. One of them asked us if we were tennis coaches (the Techne Tennis logo on our shirts and pile of racquets next to us must of given us away). “Yes,” we said, and we asked what they did. One of them was a professional boxer and the other a strength and conditioning coach. How fortuitous. Maybe we could get a good look at boxing up close?

It turned out that the boxer sitting next to us was not just any boxer, he was Olympic gold-medalist Luke Campbell. Luke represented England in the 2012 Olympic Games in London, and won the bantamweight gold medal. Now he is a professional looking to improve his craft and become world champion. Luke was in Miami because he was training for a few weeks with a well-respected Cuban boxing coach named Jorge Rubio. In boxing circles, Rubio is considered a master coach of southpaws (Luke is a left handed boxer), and has coached a few world champions.

Luke is no ordinary boxer. In fact, he is no ordinary person. While he has many great personal attributes, he possesses one quality common to all great champions. He has a never ending hunger to become better at his sport. This hunger led Luke to research and find Jorge Rubio in Miami. Jorge for years trained one of Luke’s favorite boxers, Guillermo Rigondeaux. Many boxing pundits consider Cuban-born Rigondeaux one the the best, if not the best, pound-for-pound boxers in the world. Luke’s working with Rubio was carefully calculated. If he wanted to be the best, Luke knew he needed the best coach, so he came to Miami from England a few times a year to learn what he could from one of the master coaches in his sport.

I asked Luke at breakfast if John and I could come watch him train with Rubio. He said of course, and told us a time and place. I was very excited to see the type of training Luke did, and to what degree it was applicable to the tennis training John and I were designing. But what I would ultimately see in Jorge Rubio the first morning we visited was even more fascinating, given my interest in studying people’s passion.

John and I showed up at Rubio’s gym at ten o’clock a few mornings after our initial meeting at breakfast. To call the place sparse would be an understatement. The gym was about the size of two garage bays, with a ring set up toward the center back of the space and taking up most of the available room. Along the right wall there were some hanging boxing bags and some homemade looking training contraptions made of out boating buoys and bungee cords. There was an old rowing machine and stationary bike in the corner, and a speed bag on the wall to the right as you walked through the garage door opening that served as the main entrance to the gym. It was summer in Miami, so it was hot. Stiflingly hot.

We saw Luke warming up for his workout and said hello. While John made boxing small talk with Luke, my attention turned to the silver-haired guy in the ring working with a young boxer. This man was fixated on the boxer, moving around him with cat-like quickness, and barking out instructions in Cuban-dialect Spanish. This short, wiry coach, seemed to move twice as fast as his young, fit, fearsome looking charge. It seemed like the older coach could have easily taken out the younger student with a flurry of quick shots that the younger boxer would not have even seen coming. This was Jorge Rubio. This was the man Luke had sought to improve his game in the ring and to make him a world champion.

When Rubio finished his session with the young boxer, he jumped out of the ring to greet Luke with a big hug and a smile. Luke introduced us and I could see the intensity in Rubio’s eyes. It was an intensity I had seen many times before in highly successful people. We chatted briefly, and then Luke and Rubio got down to work.

Luke is an English boxer. Jorge is a Cuban coach. Boxing is a religion in Cuba, also the country of origin for salsa music and dancing. The connection between boxing and dancing in not incidental. The two activities, it seems, are complementary. Cuban boxers dance around the ring and elude opponents while peppering them with fast, unseen punches from all angles. They are masters of deception and surprise. By contrast, English boxers tend to move methodically straight forward, attempting to overwhelm opponents with bravado and the willingness to absorb or evade punches while applying constant forward pressure. The contrasts in style are as different as the two country’s cuisines or languages. And yet, here I was watching a Cuban coach teach and English boxer. And it seemed to be a perfect fit.

Luke is great student. That morning I watched him listen intently to every word Jorge shouted, while studying every movement Jorge demonstrated. He repeated the moves – the Cuban boxing moves – over and over, sweat pouring out of every pore in the sweltering Miami summer heat. John and I noted the rotational movements Luke made when he threw his punches, and yes, they were the same as the tennis movements we were teaching. Our mission for the video content was accomplished. But what really grabbed my attention in that dingy, smelly, tiny gym was the passion of Jorge Rubio.

Here was a man who truly loved his job, who was so focused on the task at hand that a train could have driven through his gym, and as long as it didn’t disrupt the ring, he would not have noticed or cared. This was passion in action in the purest form possible. It was singular and joyful. Rubio’s energy was magnetic as he screamed “Aaayeee!” every time Luke got it right. This was the power of a great coach to harness the passion of a great athlete.

After Luke and Rubio finished their workout, I mentioned to Rubio that I had seen very few people in life with his focus and passion. He smiled and laughed as he said in his heavy Cuban accent,” Robert, I love boxing more than my wife. But it’s okay. She knows.” Not knowing Luke well at that time, and seeing the level of passion Jorge brought to sport, I thought to myself, “Luke has found an amazing coach who will definitely change his life in and out of the ring.”

Being a good host and lover of Miami, I spent quite a bit of time with Luke and his strength coach during the rest of that training camp. I showed them the sights of Miami, and ate a few meals with them. During that time, Luke expressed a keen interest in business, and was constantly asking about topics related to marketing and sports. He seemed like an intelligent and driven young man with a bright future, and clearly wanted to maximize his opportunities during and after his days in the ring.

We must have clicked, because a few weeks after he returned to England, Luke called me and asked if I would consider becoming his manager. It was a possibility for me, but I would need to know more about him and his support team and family before making a commitment. Athletes can be tricky to work with and the people they spend time with outside of the arena usually gives you an accurate picture of their character. So I flew to England to meet his family and friends. After a week in Hull, Luke and I agreed to work together.

My role as Luke’s manager would not involve the day-to-day organization of his life, as is the case with most managers. I would function more like mentor and business advisor, which was perfect for me. I didn’t accept the job for monetary gain, but rather to help Luke organize his thinking about his life and career during and after boxing. I had only the cursory knowledge about his sport that I picked up from the boxing sessions I did weekly for fitness over many years, and my observations of the sport as a fan. But I knew about high level sports training and competition from my years playing tennis. And Luke’s coaching situation bothered me from day one.

Rubio was only Luke’s part-time coach when we met. He still had a full-time coach at home in England, one he’d had since his Olympic training days. The full-time coach was the polar opposite of Rubio. He was a rather aloof, passionless Englishman, who seemed to have a clinical, detached style of working with Luke. It seemed to me, when I visited Luke in England and watched him train with that coach, that Luke was just another boxer in a long line of boxers he coached. It felt like he was doing a “job”, going through the motions to collect a paycheck.

In contrast, Rubio, the part-time coach, was an impassioned Cuban who lived and breathed boxing. His sole goal in life was to make world champions. His reward was winning. He guided Luke through his lessons the way a father imparts wisdom on a son, with a sense of urgency to pay close attention because the lesson could be life altering. His focus on getting Luke to do things right, and repeating them until he did, was unwavering. The contrast in coaching styles was stark.

As I got to know Luke better, and observed the dual-coach dynamic Luke was experiencing, I could see that it was creating tension in Luke’s mind, given that the two coaches had vastly different approaches to boxing. I was concerned for Luke, not because I knew much about boxing at the time, but because I knew it was hard for any athlete to have two coaches who each have different approaches and techniques. It’s like having two bosses at work giving two different sets of instructions on how to get your work done. Who do you listen to?

Luke’s next camp was the first of the camps where we had an athlete/manager relationship, and Luke stayed at my house in Miami while training. As expected, he was dedicated and disciplined, and trained hard six days a week. He was meticulous with his diet and sleep routine, and didn’t go out after 9pm or drink alcohol. He was focused on his passion – to be the best boxer possible and maybe world champion one day. But something seemed off one day during camp and I asked Luke, “When you are in the ring and faced with a tough situation, who’s voice are you listening to for guidance, Rob’s (his English coach) or Jorge’s?” He looked at me with a quizzical expression and said, “I don’t really know. They tell me to do different things.” Wow. Unfortunately, that was the answer I expected.

I sensed there might be a big problem with the coaching set up, but I didn’t pry further. I was just getting to know Luke and the sport of boxing, so I tried to stay in my lane as manager. I only mentioned to him that in the future, he might consider working with one coach full time (I had a strong bias for Rubio, but that was based on observing his passion and chemistry with Luke, not any special boxing insight that I had. I was new to boxing after all, and didn’t feel qualified yet to influence Luke in this area).

Six weeks of camp passed, and Luke returned to England to finish his preparations with his English coaching team. I spoke to Luke every few days to see how things were going. He sounded stressed and distracted leading up to the fight. Little, insignificant things were annoying him. His daily schedule seemed uncertain and he seemed unclear about his training and diet. I would normally go to the fight in England, but Luke called a few days before and said he hadn’t made any flight arrangements for me. Odd I thought. He was usually quite detail oriented with everything. So, I stayed in Miami.

The night of the fight I awaited news about the result. His opponent was an experienced French boxer named Ivan Mendy. Mendy was a tough opponent for Luke, a good test on his way to chasing a world title fight in a year or so. He was a cagey veteran fighter who could push Luke up a level, but was not expected to win by the boxing cognoscenti. Luke suffered his first loss as a professional that night, a twelve round decision for Mendy. Watching the fight on television, I could see that Luke looked vacant and slow, like he really did not show up to compete, let alone win. It was clear that something was amiss. I waited for his call.

The next day he called me. Luke was stung by the defeat, not so much because he lost but because he knew he had not prepared properly for the fight. The dual coach situation I feared had proven to be a big weakness that night and would be an unsustainable situation if he wanted to become a world champion.

He called me again a few days after the fight and said he was making some changes to his team. He was moving to Miami to train and was going to be working with Jorge Rubio full time. He was picking one coach to direct his training efforts, and he picked the one with amazing passion and personal commitment to winning titles. I was thrilled with his choice, because I knew the chemistry between Luke and Jorge could be the missing link for Luke, the thing that could propel him to the next level.

I suggested to Luke that I visit Rubio to deliver the news and to get a commitment that Luke would be his number one priority. At the time, Rubio was training a handful of other fighters that could have posed a distraction. Luke wanted full-time commitment – no more part time coaches. We wanted Rubio to use all of his passion to direct Luke’s ascent to the top of the sport.

As Rubio and I sat in his kitchen, he told me that his goal in life is to make world champions and that of all the fighters he was currently working with, Luke had the most potential to fulfill that level of achievement. He said that Luke would be his number one priority and that he was certain that he could take him to the top of the sport within a few years. I looked into his eyes and felt the serious intent and passion as he spoke. Ok, Rubio had the job. I called Luke and we made it official.

The first year and a half of Luke’s partnership with Rubio, Luke won five fights (four early or mid-round stoppages and one decision) against top-level opponents and two titles. He is now the leading contender for the WBC lightweight world title belt. Jorge and Luke are an amazing team. Jorge makes Luke laugh and dance salsa, and, most importantly, focus on improving his boxing skills. Luke lets Rubio impart his extensive boxing knowledge in every training session, passing his wisdom day after day and getting Luke prepared to become the world champion. Luke is like a sponge at the gym, soaking in the teaching of his incredible, passionate coach.

It’s been a perfect match of athlete and coach from day one. I’ve seen Luke’s passion and enjoyment of boxing soar, and I have watched his confidence grow with every victory. The continuing Luke Campbell/Jorge Rubio story is a great example of how a coach can help ignite and harness passion in an athlete, passion that might otherwise be stifled to a degree that prevents the athlete from ever fully leveraging his skills in pursuit of his dreams. I can’t wait to see how the rest of the story plays out!

So how about you? What coaches have you had that used their passion to make an impact in your life?

Take a few minutes to complete the exercise below and see how your coaches might have helped ignite passion in your life.

Passion Journey Exercise #4

Take out a piece of paper and write down the answers to these questions:

- In which ways have I been influenced by my coaches, and has that influence been positive or negative in my life?

- Name one or two coaches who have had the most influence in my pursuit of a passion in life. What is the passion and why is it so meaningful to me?

- Has a coach ever encouraged me to pursue or discouraged me from pursuing a particular passion?

- Have I ever had a coach who made a life-changing impact on my life?

- Have I ever observed a coaching relationship that clearly resulted in and exchange of passion? What can I learn from that exchange?

- Do I pursue any passions in my life today that I would not have pursued if not for a particular coach? What is that passion and who was that coach?

Use the answers to these question to explore your motivations for pursuing your passions. Is there a passion you have today that was stoked by a particular coach? How did they help you ignite that passion? Retrace those steps and see if you can rekindle the feeling that got you hooked on that passion. If it’s a passion you’ve set aside, but still have, see if this exercise can help you bring it back into your life. If you are a coach, maybe this exercise will help you ignite passion in the athletes, executives or other people you are helping.

(Come back next week when we will conclude Chapter 2 by exploring other influential people that have instilled or ignited passion in your life!)

Until then, let your passion create your life.

Robert (aka The Passionist)

by Robert Mazzucchelli | Apr 22, 2017 | Lessons From The Passionist

(This in installment #8 of Lessons From The Passionist: How To Turn Passion Into Purpose To Create Greater Meaning and Joy in Your Life. Last week we explored the influence of friends. This week we look at teachers, and how they can help ignite and develop our passion. Maybe you have had an influential teacher somewhere in your educational experience?)

Teachers we encounter during our school years can have significant influence on our ability to harness passion in our lives.

All of us have had a teacher or two somewhere in our past who made an impression and helped shaped our life in some way. I’ve had a few at various points in my educational journey, each of whom demonstrated enormous passion and increased my excitement about learning, while opening my eyes to possible ways I could create a fun and amazing life for myself by pursuing my passions. Three stand out.

I should preface this section by acknowledging that until about tenth grade, I was reasonably disinterested in school and viewed it as a necessary evil I had to endure until I could get to the hockey rink, baseball field or tennis court. My heart was set on becoming a professional athlete when I was young, and school was just the nuisance I was obligated to attend because my parents and the state said so. Had it been up to me, I probably would have preferred to spend all my time pursuing the sports I loved. Thankfully, I had tough parents and a respect for the law, or I probably would not be writing this book today.

My tenth grade english teacher at LaSalle Academy was a guy named Michael Mosco. He was a short, wiry, well-dressed, brown-haired guy who spoke with excitement and energy all the time. His passion for words and sentences just oozed out of him as he paced back in forth in front of his classroom. I had always been a decent writer (my mother posted “grammar rules” signs in the kitchen when I was growing up, so English was drilled into me and my siblings when we were young). English was a class I tolerated and often coasted through with little extra effort required. But this time, things felt a bit different. I sensed I might have to really think and work to do well in Mr. Mosco’s English class.

I walked into the classroom on the first day of school and written on the board was a question — “What is universality?” Okay. I looked at the question, took a seat at a desk in the front of the room, and joked around with some friends that I hadn’t seen all summer. We were immediately startled as Mr. Mosco asked an urgent voice, “What is universality?” “What is he talking about?”, I thought. My classmates and I just looked at each other. We were all probably thinking the same thing, which was, “Who is this guy and why is he so excited at 9am on the first day of school?” Was he a BIG coffee drinker? No, it turned out – just a guy with an incredible passion for teaching English.

Mr. Mosco was asking a deep philosophical question to a bunch of kids who had probably never thought that deeply in their lives. He was challenging us to think, while also putting us on notice that his class would not be one in which we could coast or just hide in the back of the room and get by. He walked between the rows of desks that day and asked each and every one of us what we thought about his question. He got in our face. What did we, a group of fifteen and sixteen year-olds think about universality!? Really? The question and the teacher’s passion for exploring the answer somehow woke up my brain in a way no teacher had up to that point, and I started to think and engage in a conversation unlike any I had had in school before. We were debating, for forty-five minutes, the meaning of a WORD. ONE word. We were learning. We were growing. This was actually cool. And fun.

That year in Mr. Mosco’s class, reading great books and participating in long conversations, debates and arguments, gave me the first glimmer of hope that maybe school could be more than just sitting in class waiting for the bell to ring. It was like being in John Keating’s class (Robin Williams’ character in Dead Poets Society – “carpe diem, seize the day…”). Maybe I could be engaged and excited by something other than chasing a tennis ball around a court and hitting it in places my opponent could not reach. Maybe school would have a purpose beyond wasting the daytime hours during which I preferred to be outside playing my favorite sport.

For forty-five minutes, three-times a week, over the course of a few months, one man with a passion for words and sentences changed my perception of high school and learning in general. He opened my eyes to thinking about words, something I took for granted until then, and how they convey meaning. He introduced me to Elements of Style, the seminal book on good writing that still sits on my desk and is embedded in my brain. He taught me to enjoy discussing and debating ideas and concepts, a process and skill that would be essential years later in my advertising career, where every idea and word used can make a huge difference on the impact the work will have for clients. Mr. Mosco transferred his passion to me during my time in his class. The Chain of Passion was at work again.

When I arrived at the University of Richmond to start my freshman year, I had only a vague idea about what I was there to learn. I hadn’t even given a possible major a lot of thought when picking the school. I went there to play tennis, which is like a full time job in college, and believed that I would spend several years after graduation playing professionally. What happened after tennis, I thought, would unfold in due time. I liked business, but had no concrete plans or keen academic interest I was excited to pursue. But I was always making money with small businesses as a kid, shoveling snow, stringing tennis racquets or detailing cars. So I figured I would most likely major in business and hope for the best.

I took the core classes during my freshman year to qualify for the five-year, juris doctorate/MBA program offered at the University of Richmond (the program sounded efficient to me, more bang for the time I would have to spend in school). I signed up for an ambitious schedule of accounting, statistics and logic classes, along with required French and Biology classes. All classes that I hated. As fate would have it, I also signed up for two elective classes: The History of Entrepreneurship and Introduction to Speech Communication. I was allowed to choose these classes my freshman year because I had scored high enough on a assessment test to exempt me from the required basic freshman English classes. Thanks, Mr. Mosco (and Mr. Scott, a great English teacher I had at Kent School. He taught me the life lessons contained in Melville’s Moby Dick, one of my favorite books. Coincidentally, his bother had been a professional tennis player and writer).

The speech class was taught by Dr. Jerry Tarver. He was an amiable, good humored, slightly rumpled, graying man in his early fifties who wrote speeches for CEO’s and politicians when not teaching. His somewhat high-pitched, southern-accented voice had a unique way of cracking when he spoke, which for reasons I can’t explain, kept your attention riveted on what he was saying. He was always smiling and joking. He was a passionate and engaging man who loved his subject, and had even written a book on speechwriting, which was the textbook for another one of his classes that I took during my senior year. After a few speech classes with Dr. Tarver, I saw my future standing in board rooms making presentations (about what, I still had no idea). Because of his influence, I decided to change my academic focus from business/law to business/communication (I ended up majoring in Communications and Economics).

Why the switch? It was simple. My passion for words and language far outweighed my passion for numbers and rigid legal precedents. I was, I discovered, a creative person at heart. Dr. Tarver taught me the power of using words and speech effectively. He sensed that I loved making speeches and communicating with people, and he encouraged me to improve my skills in this area. I do love persuading people to do things, and have made a career of it. Apparently, I was always persuasive – as my family and friends are quick to point out – but I didn’t understand why or how. Studying communication gave me the tools to be more intentional and focused in my speech. After a few classes and some guidance from Dr. Tarver, who became my academic advisor, there was no doubt what I would be doing for a career after my tennis playing days ended. I would be using words and ideas. Writing and speaking would not only become my craft, it would become my passion.

The University of Richmond added a student speaker to the commencement program the year I graduated. It was the first time they had done so, and the speaker was to be chosen by a competition judged by a panel of professors and administrators. With the help of Dr. Tarver, I wrote an excellent speech and entered the competition. It was a thoughtful, hopeful speech that challenged my fellow graduates to do something meaningful with their lives after leaving Richmond. The process of writing and presenting the speech even made me think I might pursue a political career someday (am ambition that was quickly discarded after living in Washington D.C. for seven years and meeting actual politicians. I’ve met criminals I trusted more!). I felt I had a chance to win the speech competition. When the five finalists were chosen from hundreds of submissions, I was among them. But when I saw the list, my heart dropped. Of the five finalists, I was the only male student.

I could have written the Gettysburg address and lost that competition. I knew the school would not pick the only male finalist on the list. It was still the pre-PC era, but I knew I would lose and I did. When I pressed Dr. Tarver, who was on the speaker selection committee, about the results, he obliquely confirmed my suspicions and told me I had written and delivered the best speech. Of course, that was only his opinion. But I knew my speech was good. That loss, and the lesson it taught, me did not diminish my passion in any way. After my tennis career was over, my speaking skills would be put to good use.

I sadly don’t remember the name of the professor who taught the History of Entrepreneurship. I wish I did because I‘d like to thank him. I was vaguely familiar with the word entrepreneur back then, but unclear about its actual meaning. I knew an entrepreneur was someone who started businesses. The word wasn’t as thrown around in pop culture in 1981 the way it is today. Entrepreneurs were not yet the rock stars they are now. But I liked starting businesses, so the class seemed like a good fit. The professor, unbeknownst to me at the time, would change my life. Here’s how: about three weeks into the class, he assigned a book for us to read called Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise. As the title suggests, it was a book about how companies developed their structure and strategy. Did strategy create structure, or did structure dictate or inform strategy? The book compared and contrasted Ford and General Motors as examples of two car companies that developed and operated very differently in pursuit of the same objectives. The details of the book aren’t important here, but my experience with this book in this class, and how it unleashed a passion, is important.

I knew a little about the corporate world prior to entering college because my mother had bought me a subscription to FORTUNE magazine when I was seventeen (why she did, I still wonder but she obviously really understood me and prepared me for my life – an amazing mom). I had taken a job teaching tennis at Woodway Country Club in Darien, Connecticut during the summer between high school and prep school (I did a post graduate year at the Kent School because a tennis related injury prevented me from attending college immediately after high school, a story I will tell in more detail later in the book when we discuss how to sustain passion in the face of setbacks…).

During my three hour train rides from my home Providence to the club in Darien (a suburb of NYC) every weekend, I would read FORTUNE cover to cover. Like a sports fan following their favorite athletes, I studied the performance of the CEO’s of all the top companies. This was my first exposure to the business world. My father was a dentist, so business wasn’t really discussed at the dinner table. I had to teach myself, and was motivated to do so that summer because almost all of the people I was teaching were major business executives. In fact, I ended up teaching a few of the CEO’s I read about in FORTUNE that summer at Woodway Country Club. One, David Kearns of Xerox, even ended up being my college commencement speaker!

Like my mom, the professor teaching the History of Entrepreneurship sensed my passion for business and paid particular attention to me in class discussions. The day he assigned us to read Strategy and Structure, he asked me to meet him after class. He told me that he felt, after a few weeks of interaction in class, that I had a unique ability to understand the concepts of entrepreneurship. He wanted me to teach the next few classes based on what I would learn from the book. Whoa! Talk about trial by fire. I was eighteen, new to college, and this guy wanted me to teach the class. Great. Now I really had to focus on the content of that book.

I devoured the book, organized my thoughts and reviewed my syllabus with the professor (damn, I wish I remembered his name). He made a few changes and then it was show time. The class had about fifteen students, so it wasn’t too intimidating. I’d given tennis clinics to bigger groups of people. As I started to talk about the content of the book, and ask my fellow students questions, things just flowed. The time flew by. I felt fully engaged in a way that I had only felt on the tennis court up to that point in my life. I enjoyed the topic of entrepreneurship and I liked teaching people. My passions for business, teaching and leadership were stoked in this class, and I owe that professor a big hug.

By the time I reached my junior year in college, I was pretty clear about my life. After graduation, I would pursue my passions for tennis and entrepreneurship. My core business skill would be communication (which is exactly how things turned out). Frankly, I was ready to leave school and get started on life at that point. My senior year of college seemed like a waste of time in many respects, but I begrudgingly endured it (even sitting through the graduation watching another student give the speech I thought I deserved to be giving). Such is life. It has all turned out quite well, and the learning and adventure continue to be fueled by my passions.

We hear people talk about the impact teachers have on students. Sometimes it sounds obvious and trite. I can say that from my experience, the impact is profound in many ways. For me, and for many people I have interviewed, teachers have been a major source of inspiration. They often inspire passion, either by introducing a student to a new passion or helping to stoke the flames of an existing passion. Or sometimes, as in the case of Jerome Sordillion of Cirque du Soleil, a teacher can be so negative about the odds of success in pursuing a passion, that the student works hard to prove the teacher wrong! In either case, passion is fueled and the result can be a fascinating life.

Passion Journey Exercise #3

Take out a piece of paper and write down the answers to these questions:

- In which ways have I been influenced by my teachers, and has that influence been positive or negative in my life?

- Name one or two teachers who have had the most influence in my pursuit of a passion in life. What was the passion and why is it so meaningful to me?

- Has a teacher ever encouraged me to pursue or discouraged me from pursuing a particular passion?

- Have I have had any teachers that have made a life-changing impact on my life with regard to my pursuing a passion?

- Do I pursue any passions in my life today that I would not have pursued if not for a particular teacher? What is that passion and who was that teacher?

Use the answers to these questions to explore your motivations for pursuing your passion. Is there a passion you have today that was stoked by a particular teacher? How did they help you ignite that passion? Retrace those steps and see if you can rekindle the feeling that got you hooked on that passion. If it’s a passion you’ve set aside, but still have, see if this exercise can help you bring it back into your life. Who knows where the process might lead?

In the next section of Chapter 2, we’ll explore the influence coaches can have on our passion.

Until then,

Let Your Passion Create Your World!

Robert (aka The Passionist)

by Robert Mazzucchelli | Apr 13, 2017 | Lessons From The Passionist

(Installment #7 is the continuation of Chapter 2: What Drives You To Do The Things You Do from my book, Lessons From The Passionist: How To Turn Passion Into Purpose To Create Greater Meaning and Joy in Your Life. In this installment, I explore the influence friends have on our ability, desire and courage to follow our passions in life).

Early friendships, both close and casual, have enormous impact on our attitudes and behaviors. Therefore, they can also have a significant and life-changing impact on our ability to harness passion in our lives. My own experience serves as a crystal clear example.

I introduced you to my great friend, Steven Roberts, earlier in the book. I didn’t go to school with Steven and didn’t even live close to him in Rhode Island, where we both grew up. We met at a tennis camp and shared the same tennis coach for part of our junior tennis careers. We traveled to tournaments together as kids, we practiced together every week, and we even drove Steven’s white diesel Puegeot across the country during on summer break from college, playing in tennis tournaments each week as we explored the United States, city by city, town by town. Suffice it to say, we’ve spent a lot of time together. We’ve been friends for over forty-years, and we still talk every week.

Steven and I had a saying when we were young: “think big, be big!” I’m not sure exactly when we adopted that saying as our mantra, but for years we would repeat it, and we both knew what it meant. It was our way of saying that even though we were from the smallest state in the United States, and not the epicenter of tennis or any industry we hoped to be in at some point in the future (it ended up being marketing and advertising), we did not want any limits set on our potential achievements. “Think big, be big” was our battle cry, our refusal to let anyone or any circumstances dictate how we were going to live and who we were going to become.

As a result, we both left Rhode Island for college. I went to the University of Richmond on a tennis scholarship and Steven went to California, first attending the University of California at San Diego and then Berkeley. We both traveled the world playing in professional tennis tournaments in the summer, something only a handful of tennis players from Rhode Island did (although there were a few great one. My frequent childhood sparring partner, Jane Forman, became a world top-fifty professional who battled tennis great Martina Navratilova on Centre Court at Wimbledon). Our tennis adventures were the first manifestation of our “think big, be big” slogan.

After we both realized that a future in the business of playing tennis was unlikely, we opened a sports marketing company, Pinnacle Promotions, together in Alexandria, Virginia. At the time, Washington, DC was a major center for sports marketing companies, and we wanted to play with the big boys. So we set up shop in their backyard. Forget the fact that we had no experience, no money and few contacts to help us get started. “Think big, be big” would carry the day. And it did.

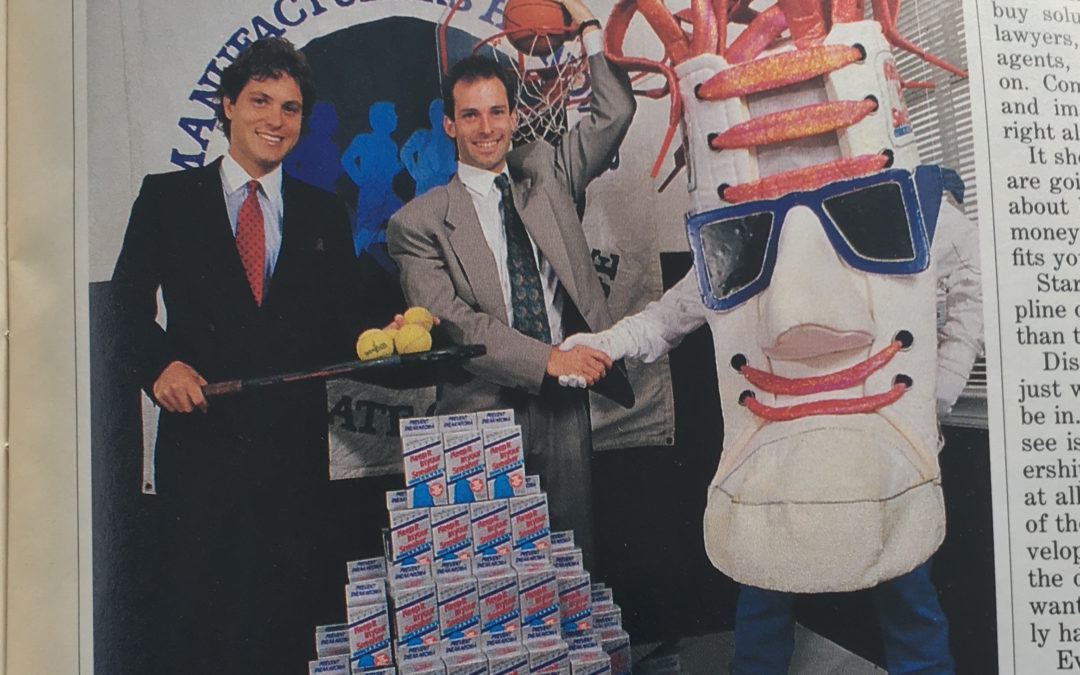

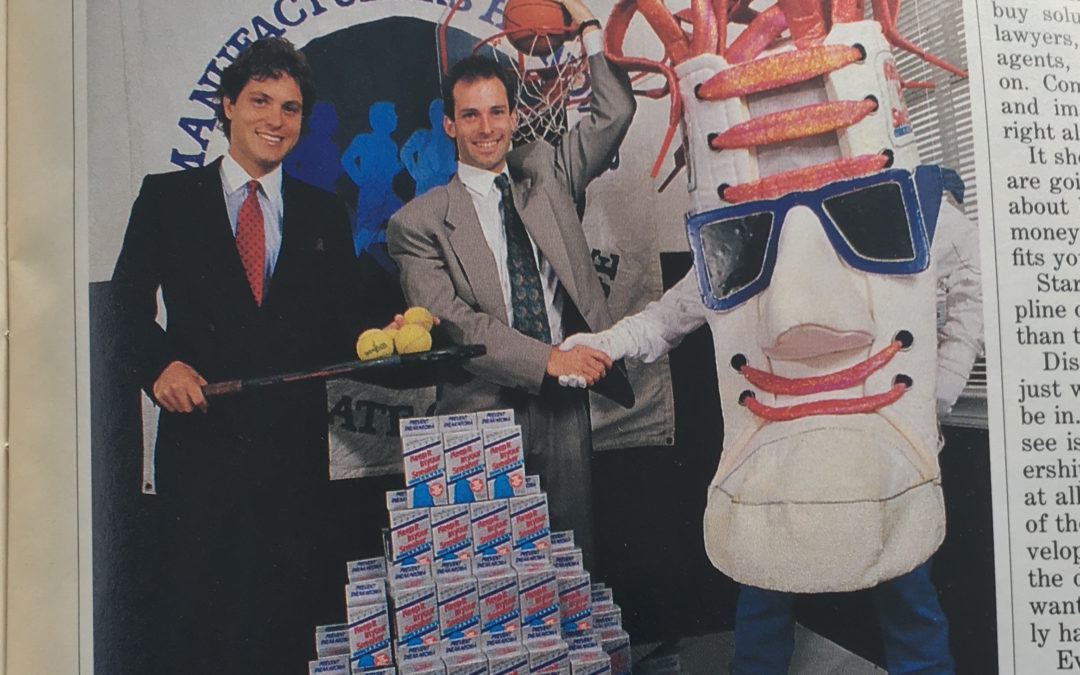

Within one year, we landed a national promotion contract to promote a new product, Sneaker Be Cool, a short-lived sister product to the famous Gold Bond Powder that was then owned by Block Drug Company. Through that contract, we introduced consumers to Sneaker Be Cool at running races and events across the United States, rubbing elbows with other big brand sponsors and sports marketing experts, and getting one step closer to the big time.

One satisfying note on winning the Sneaker be Cool business was that the company we beat out to get the account was Advantage International, the major sports marketing firm whose job offer I had turned down to start Pinnacle Promotions with Steven. When I declined their job offer, which was an entry level project management position, the person offering me the job said, in a mocking tone I might add, that I was crazy to even consider trying to compete with them by starting my own company. In the early days of the sports marketing industry boom, which created great athlete/brands like Arnold Palmer, Bjorn Borg and Air Jordan, people who wanted to be in the business would have given their left arm to get that job offer with that company. But I turned them down because I believed I could do more on my own. Crazy? Maybe. But the offer as an entry level project manager didn’t fit the “think big, be big” philosophy.

I was young, had nothing to lose, and wanted to conquer the world of sports marketing with innovative thinking, not just work as an entry level “step and fetch it,” a position that might last a few years before I could make a meaningful thought leadership impact on the industry. I was impatient and willing to put in whatever time and effort were required to succeed. So Steven and I started Pinnacle. Although we ultimately didn’t overtake any of the big companies in the industry, our small successes created bigger successes. We made a name for ourselves as being innovative and creative thinkers. This reputation helped us win business in other areas of marketing, not just sports in sports and event sponsorship. Our small company’s success was big enough to create new and bigger career opportunities for me and Steve. About seven years after I declined the Advantage International offer, I ran into the guy who offered it to me at the U.S. Open Tennis Championships in NYC. I was then president of Bates Promotion Group with an office in the Chrysler Building and several leading brands as clients. He still had the same job as when I interviewed with him. Imagine where I would have ended up had I taken his offer! Probably not sitting here writing this book. Score one for “think big, be big.”

The point of this story is that my friend, Steven Roberts, influenced my life view and I his, in that we shared our “think big, be big” philosophy and supported each other in our efforts to live life true to our beliefs and dreams. We fueled each others’ passion to live not by anyone else dictates, but by our own. And we continue to support each other to this day.

I mentioned Cirque du Soleil star Jerome Sordillon earlier. When we spoke about how he became a world-renowned circus artist, he told me that it was his best friend who told him to quit the construction internship he hated. It was that same friend who asked him one day to join him on some vaguely described trapeze adventure two hours away from their home in Lyon. That adventure on the trapeze turned out to be a job interview with Club Med, where Jerome was immediately hired because of his athletic skills. At Club Med, he met a women who also recognized his enormous talent. She suggested he attend apply to the prestigious Ecole National de Cirque in Montreal, which only accepts twenty students a year out of thousands of applicants. He applied and was accepted. Upon graduation from that school, he was found by Cirque du Soleil and hired to be a featured performer with arguably the best circus performance company of all time. His friend was the catalyst for the whole chain of events that changed Jerome’s life. Who knows where Jerome might be had he not had that friend?

Pay attention to your friendships, past and current. They reveal a lot about your own life and just might be an important key to whether or not you are following your passion today!

Passion Journey Exercise #2

Take out a piece of paper and write down the answers to these questions:

- In which ways have I been influenced by my friends, and has that influence been positive or negative in my life?

- Name one friend who has had the most influence in my life. What was the influence and why is it so meaningful to me?

- Has a friend ever encouraged me to follow or discouraged me from following a particular passion?

- Do I have any friends that I feel have made a life-changing impact on your life?

- Name one friend that I have influenced in some way? How did I influence them?

- Do I pursue any passions in my life today that I would not have pursued were it not for a friend? What is that passion and who was that friend?

- Do I have any friends in my life today who are encouraging or discouraging with regard to me pursuing my passion? Who are they? What are there reasons for their feelings? Do I believe them?

- Are any of my friends helping me or holding me back from pursuing my passion today?

Use the answers to these questions to reflect on your own life and attitudes. Were you encouraged by your friends to develop and pursue your passions? Are there passions you had when you were younger that were squashed by a friend, that you would like to rekindle now? Are there thoughts or attitudes that were influenced by your friends that are holding you back (or helping you succeed) in pursuing your passions or attacking life with a passionate attitude?

Depending on your answers to these questions, you might be really lucky and have a great supportive friend network. Or you might need to rethink which friends are helping or hurting your ability to create the life you want. Give it some thought and make sure you are surrounding yourself with the right people everyday.

Next week, in Installment #8, we will explore the influence of teachers in out life. Until then…

Let Your Passion Create Your Life!

Robert (aka The Passionist)

by Robert Mazzucchelli | Apr 9, 2017 | Making Dreams Come True

5 Keys to Successfully Managing a Young Professional Athlete’s Career

Managing professional athletes successfully requires a bit of science and a bit of art. The stars of today’s sport world are highly visible characters, some of whom rise to “brand” status, some of whom toil in virtual anonymity game after game, known only to the most avid fan. As manager, the advice we give early in our clients’ careers can have an immense impact on the rest of the athlete’s life. To set a strong foundation, I adhere to the following five keys:

- Know the Athlete as a Person. This sounds obvious, but many managers take on athletes who look like a good payday. Period. This is short sighted and hurts you and the athlete. Unfortunately, athletes aren’t like other products or business assets. They are human beings, with all the unpredictability that comes with being human. Athletes who are beginning their professional careers are usually in their early 20s, and many of them are just experiencing financial success and notoriety for the first time. The one’s who are not well-grounded will find this an unsettling time, and a potentially dangerous transition period where bad habits can emerge. Or it can be a great time to lock in great habits that will serve as the basis for a lifetime of success and fulfillment in and out of the sports arena. Before signing on to manage an athlete, I recommend spending some quality time to assess WHO you will actually be managing. Try to find out what makes them tick, why they play their sport, what short and long term goals they have in their sport after they’re done competing, what other interests they have beyond their sport, what other talents they have aside from their sport, what they would do if they didn’t play their sport, and what they want to do with their notoriety to give back to a world about to give them a big payday. Also, spend time with their family and friends to find out how they were raised and what other influences might come into play throughout their careers. The more you know before starting the job, the more effective you will be (and you might decide to walk away to avoid a waste of your time and giant headache).

- Think Long Term, Then Think Short Term. I think a twenty year planning horizon is not too long. Consider this. Most young athletes will have 3-10 years of productive playing time, depending on their sport and injuries. A rare few, and mostly the superstars, will last as long as 15-18 years. As a manager, you need to help your client maximize their relatively short career cycle, while advising them on how to best transition to a non-playing career at retirement. Start with the long view. Ask them what they want their life to be like in 20 years. Family, kids, houses, day-to-day schedule. Try to get them to create a detailed picture of their future when their playing days are over. Once they have imagined their life in 20 years, let them know what resources they will need to have that life and begin to work backwards to today, planning the activities that will be necessary to make their vision a reality. 20 years seems long, but it goes by fast. Suppose your client plays a sport with a 5-year average playing life. Only 5 years of their 20-year vision will be spent on the field creating maximum income and celebrity status. What they do during those 5 years is critical to determining the opportunities that will open up to them for the future, but its only 25% of the 20-year period. You need to help them plan for the variety of best-case, worse-case scenarios that may play out during the course of their lifetime.

- Never Sacrifice Sport Performance for a Non-Sport Commitment. This can be a tough one for managers and athletes who are constantly being barraged with offers to promote a product or make an appearance for a quick fee, especially knowing the finite earning time period of the athlete. This is why long-term planning is an important first step when beginning a management relationship with an athlete. It will help reduce the temptation you both might have to accept what looks like easy money, when the deal might actually compromise the performance of the athlete. And performance is what unlocks the door to all the spoils of an athlete’s career. Losers don’t usually end up on the Wheaties box. Winners do. So my rule is to advise clients to make the training schedule for optimal performance (i.e. winning) first (practice, workouts, recovery, sleep, diet, film, etc) the priority. Then see what windows of time are left for sponsor activities, appearances, charity work and other non-sport related activities, and then maximize those open time windows with activities that support the long-term career plan. As the manager, you need to stay disciplined and help keep your client on track toward a successful present and future.

- Foster Relationships to Help Clients Achieve Long Term Goals. If your client has a goal to own a restaurant chain after they retire, chances are they will not have the expertise to manage that kind of business immediately upon retirement (and maybe never). They will need help. They will need partners. When an athlete is in the prime of their career, access to people is easy. The time to meet people who can help after retirement is during the playing career. If you wait, it can be too late. So, as a manger, one of the most important jobs is to make sure your client meets all the people he or she will need to know when they start winding down their playing career and start looking toward the next phase of their life. If you have taken the time to understand their personality and goals, it should be very easy to identify who the best people are to meet in any field of endeavor, and call them up to say, “my client (star athlete) would like to meet you.” If you are managing an athlete who is well known and has a good reputation, almost everyone will take the meeting. If you do this throughout your client’s playing career, they will have hundreds of contacts that can help them transition to whatever post-playing career they may be interested in pursuing.

- Use Short-Term Deals to Get Long-Term Deals. Earnings from sponsorships are a critical part of many professional athlete’s income, especially individual sport athletes. Yet, unless you are managing a superstar, sponsorship deals can be difficult to secure, and securing the right kinds of deals can be even trickier. What do I mean? Brands sponsor athletes based on several factors: visibility, likability, reputation, fan base size, media exposure, personality fit and the ability to utilize the athlete in a variety of ways to drive brand exposure and incremental sales. Sponsors have many options of athletes to choose from (along with sponsoring teams and events), so getting your client the right deals takes some planning. Start by listing the appropriate categories and brands that fit your client’s brand persona (every athlete is different has a unique “Brand Essence”). For example, is your client a better fit for coffee or soft drinks? Nespresso or Sprite? You should have a sponsorship wish list of about 10 product categories and 3-5 brands per category. Then you need to determine why your client could be valuable to each brand (what does your athlete offer from the list above?). Chances are, unless you are managing the next Michael Jordan or Roger Federer, you will have to build toward the ultimate deals you want. For example, in what I call Phase 1, you may have to make smaller, short-term deals with a second or third choice company in a particular category to put your client “in play” in the category. Once competing brands in that category see your client, and the benefits created by the sponsorship, then you will have a better chance of making a bigger deal with the brand you really want in Phase 2. Phase 2 is characterized by a solid multi-year sponsorship deal with the brand of choice in a category. Finally, if all goes well in Phases 1 and 2, and your client keeps performing and winning, Phase 3 is the holy grail – brands bidding to sponsor your client. Not all athletes will get here, but if you get them into the sponsorship arena early and sensibly, create visibility and exposure that can be combined with successful results in their sport (and all the exposure that the success will bring), than Phase 3 becomes a possibility. You and your client should make Phase 3 the goal!

Make these 5 keys part of your management process and enjoy a long, successful relationship with your young athletes, and you will feel rewarded by knowing you have helped them focus on their important Job #1 – being the best that they can be at their sport!

(This is installment #9 of Lessons From the Passionist: How To Turn Passion Into Purpose To Create Greater Meaning and Joy in Your Life. Today we talk about the influence coaches can have on our passion, whether helping us find it or bring it back when it seems to be waning. Enjoy!)

(This is installment #9 of Lessons From the Passionist: How To Turn Passion Into Purpose To Create Greater Meaning and Joy in Your Life. Today we talk about the influence coaches can have on our passion, whether helping us find it or bring it back when it seems to be waning. Enjoy!)

Recent Comments